In April I gave the opening keynote at the software industry conference “QCon London” under the title “The Home Computer That Roared: How the BBC Micro Shaped Our World”.

The video and slides have just been released. There is also a transcript but you’ll miss the many embedded videos. I’ve given some background and further thoughts below.

These software industry conferences are a big industry in themselves. Employers of the attendees pay several thousand dollars for each ticket, typically taken as part of the training budget. The idea is that the attendees get to brush up their skills and situational awareness in a convivial setting with lots of networking opportunities.

Somewhat surprisingly given the high ticket prices, speakers are not paid for these kind of events. The idea is that we benefit from the exposure. There are quite a few regular speakers at industry conferences that use it as a very successful shop window for selling themselves as a consultant. While I enjoy public speaking, I’ve always found that putting together an interesting talk for a general audience is very demanding, and so it’s not something I’ve done very often.

The organisers wanted me to mix some nostalgia about what I was doing as a teenager along with the sort of (hopefully) searing insight into the current state and future direction of the software industry that comes with now being an old timer.

Most of the conference is structured to give attendees a choice of two or three different talks, but the keynote (and the closing talk) are different, plenary sessions that everybody is expected to attend. That meant that I had to target the talk to a technical but general audience, and not make assumptions about what they knew about life in Britain in the 1980s or how open source works today.

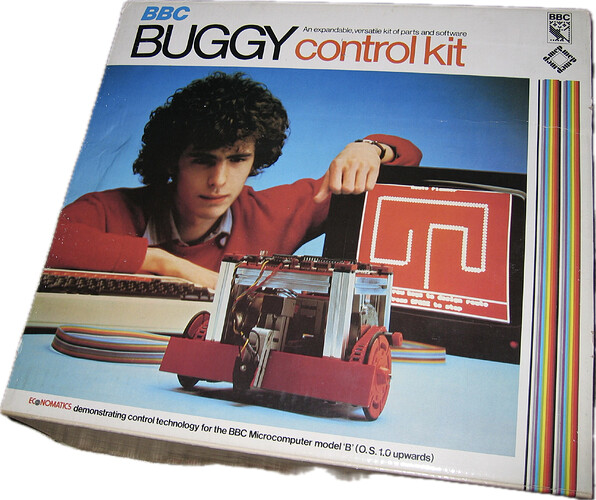

The BBC Micro was an important home computer in the United Kingdom in the 1980s and 1990s. It has a good claim to contemporary global significance thanks to the fact that its designers went on to design the ARM chip, one of the underpinnings of the mobile computing revolution of the last 20 years.

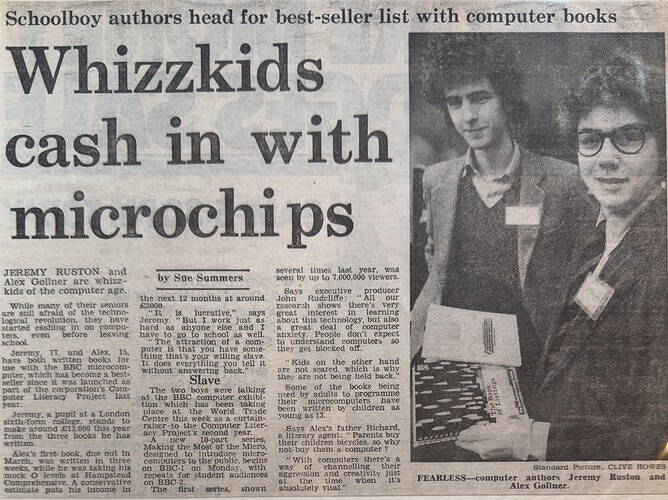

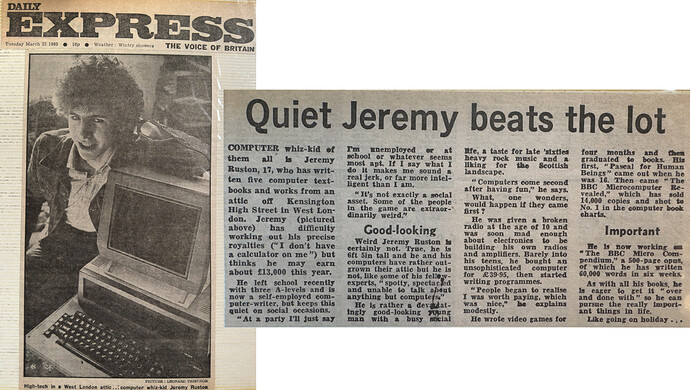

The BBC Micro was also very significant personally: it was released when I was 17, and had had a lot of experience with earlier machines. I devoured that machine, breaking it down until I understood every last aspect of its magical behaviour. I wrote books about it, made software for it, and used it to produce animations that were used on British national TV.

Despite that significance, the story of the BBC Micro isn’t where I would choose to start if I was given a free rein to speak about anything I wanted. While I loved the BBC Micro at the time, I was unsentimental and moved on to other and better computers as soon as I could get my hands on them.

So I had to work hard to weave in the story that I wanted to tell – which, of course, is really the story of TiddlyWiki and everything I’ve learnt from its users and community.

I had a few worries while I was preparing for the talk, one of the chief ones being that it might inadvertently only be accessible to people who share my historical and cultural background. Happily, I got great feedback for the talk, and was overwhelmed by kind comments over the rest of the conference.

I am left wondering what I should learn from the experience, and particularly whether the feedback might be telling me something important. For example, maybe I am missing opportunities to do this sort of thing and get paid at the same time – it might be possible to persuade the companies that send attendees to these conferences to instead spend some of that cash on getting me to address their in-house meeting.

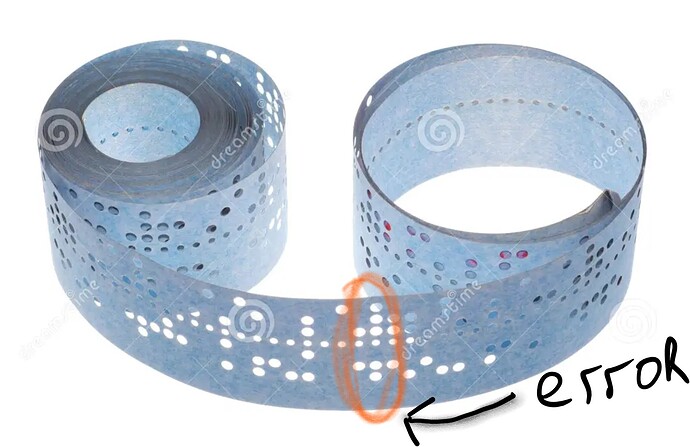

Here are some of the pictures from the slides: