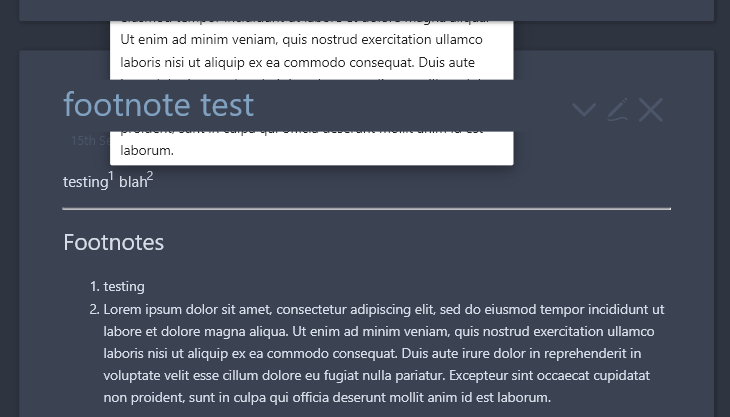

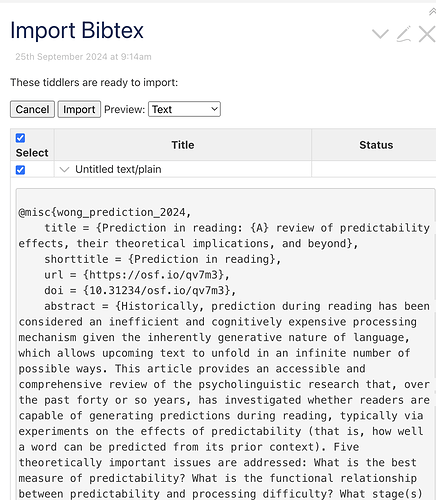

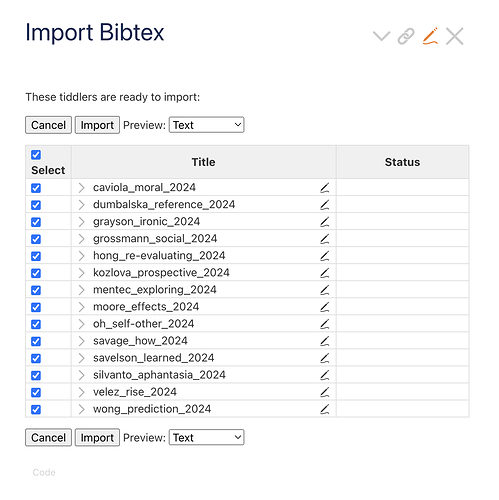

@Mohammad I can’t wait to start using this plugin! Unfortunately, when I try to paste a bibtex entry into the “Paste your Bibtex Entry here” in an empty.html + the plugin, I get the following. It doesn’t seem to recognize it as something to insert into the bibliography.

On the other hand, when i do the exact same thing in the demo website, I get this:

Any idea what’s happening? Thanks in advance!

(here’s the bibex:)

@misc{wong_prediction_2024,

title = {Prediction in reading: {A} review of predictability effects, their theoretical implications, and beyond},

shorttitle = {Prediction in reading},

url = {https://osf.io/qv7m3},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/qv7m3},

abstract = {Historically, prediction during reading has been considered an inefficient and cognitively expensive processing mechanism given the inherently generative nature of language, which allows upcoming text to unfold in an infinite number of possible ways. This article provides an accessible and comprehensive review of the psycholinguistic research that, over the past forty or so years, has investigated whether readers are capable of generating predictions during reading, typically via experiments on the effects of predictability (that is, how well a word can be predicted from its prior context). Five theoretically important issues are addressed: What is the best measure of predictability? What is the functional relationship between predictability and processing difficulty? What stage(s) of processing does predictability affect? Are predictability effects ubiquitous? What processes do predictability effects actually reflect? Insights from computational models of reading about how predictability manifests itself to facilitate the reading of text are also discussed. This review concludes by arguing that effects of predictability can, to a certain extent, be taken as demonstrating evidence that prediction is an important, but flexible, component of real-time language comprehension, in line with broader predictive accounts of cognitive functioning. However, converging evidence, especially from concurrent eye-tracking and brain-imaging methods, is necessary to refine theories of prediction.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Wong, Roslyn and Reichle, Erik and Veldre, Aaron},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {brain imaging, eye movements, predictability effects, prediction, reading, reading models},

annote = {review article of prediction in reading

},

}

@misc{savage_how_2024,

title = {How and why to read and write academic research},

url = {https://osf.io/p37zj},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/p37zj},

abstract = {This article is designed to concisely teach undergraduate and new graduate students lessons I have learned in my past two decades as a university student, teacher, and researcher (including through publishing, retracting, correcting, and republishing articles in journals with varying levels of “impact” and publication fees). Don’t just start at the beginning of an academic article/book and try to read straight to the end! Instead, I recommend starting by reading the title(s)/author(s) and abstract(s), then the figures, reading the Discussion section, and skimming/spot-checking the references, peer reviews, and data (e.g., spreadsheets, audiovisual stimuli, surveys), if available. Only once you have done this and evaluated whether it seems worth your time do I recommend deciding whether to read every word of some/all sections/chapters (and any accompanying supplementary material) or digging deeper into reanalysing/ replicating the data. I recommend writing accordingly so that most of your key information will be conveyed even if your reader only gets through your title, abstract, and figures. I discuss various strategies to improve your own academic reading/writing and the broader culture of academia, from practical (e.g., formatting and tracking references and citations using Zotero and Google Scholar, asking constructive questions rather than self-promoting comments, publishing using Peer Community In Registered Reports) to philosophical (e.g., ethical issues in authorship, citation, publishing, and funding). I explain the intended goals of academic research (to create and distribute valuable new knowledge) and perverse incentives that lead us astray from these goals (e.g., chasing prestige and funding). I conclude by posing the open question of if and how we should dismantle the current extortionary academic-industrial complex and re-design it to align with its intended goals.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Savage, Patrick E.},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {reading, citational justice, data visualisation, open science, writing},

}

@misc{kozlova_prospective_2024,

title = {Prospective and retrospective awareness of moment-to-moment fluctuations in visual working memory performance},

url = {https://osf.io/nbftr},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/nbftr},

abstract = {Visual Working Memory (VWM) performance fluctuates from moment to moment with occasional failures in maintaining accurate information in mind. While previous research suggests that individuals are more often overconfident in their VWM performance during these failures, no study to date has examined whether individuals can prospectively predict VWM performance reductions. To test the accuracy of both prospective and retrospective awareness on VWM performance, we developed a VWM bet task in which participants made trial-by-trial bets and confidence ratings on VWM performance. Across two experiments, we demonstrate that retrospective awareness is more sensitive to VWM performance fluctuations than prospective awareness, though both metacognitive abilities are far from perfect. The poor metacognitive abilities reflected a general tendency for individuals, particularly the low VWM capacity individuals, to overestimate their VWM performance. When individuals overestimated their upcoming VWM performance (i.e., prospective failures), we observed a reliable reduction of VWM performance compared to the preceding trials of a prospective failure. Moreover, this reduction in performance lingered into subsequent trials. Interestingly, however, individuals’ prospective and retrospective awareness better aligned to VWM performance after the initial occurrence of a prospective failure. This post-failure calibration was observed even without immediate feedback signaling the occurrence of a prospective failure (Experiment 2), thus suggesting a metacognitive efficiency in recognizing the initial overestimation. Taken together, our results suggest that individuals, particularly low-capacity individuals, have a limited awareness towards upcoming VWM performance. However, after the occurrence of a prospective failure, individuals adjust their metacognitive ratings to better reflect their VWM performance.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Kozlova, Olga and Adam, Kirsten and Fukuda, Keisuke},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {metacognition, attentional fluctuations, individual differences, visual working memory, working memory},

}

@misc{velez_rise_2024,

title = {The rise and fall of technological development in virtual communities},

url = {https://osf.io/tz4dn},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/tz4dn},

abstract = {Humans have developed technologies to adapt to virtually every habitat on Earth. But why do some communities develop thriving technological repertoires while others stagnate? We address this question by analyzing player behavior in One Hour One Life (OHOL), a multiplayer online game where players can build technologically advanced communities from scratch (N = 22,011 players, 2,700 communities, 428,255 playthroughs). Players are randomly assigned to a community in each playthrough and can contribute to it for up to one hour. Over time, through many players' contributions, communities can survive for weeks and amass rich technological repertoires. Thus, this dataset provides a unique quasi-experiment into how the composition of communities affects their growth and decline. Using this approach, we find that technological developments are the product of interactions between individuals and the communities where they are placed. Individuals take on jobs that align with those of their closest peers, and they selectively contribute new technologies in areas of their expertise that diverge from the rest of the community. In the aggregate, these two processes—aligning to form specialized communities, or diverging to form diverse ones—have opposing effects on the size and stability of a community's technological repertoire, and imbalances in specialization serve as an early indicator of population collapse. Our results suggest that, to survive, communities must balance between diversifying to develop new technologies, while specializing to maintain the ones they already have. Our approach provides a testbed for theories of large-scale social phenomena that would otherwise be difficult to test against real-world data or traditional laboratory experiments.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Vélez, Natalia and Wu, Charley M. and Gershman, Samuel J. and Schulz, Eric},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {computational social science, naturalistic datasets, social behavior, technological development},

}

@misc{oh_self-other_2024,

title = {Self-{Other} {Mirroring} in {Personality} {Structure}},

url = {https://osf.io/xre5s},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/xre5s},

abstract = {Humans use themselves as a reference when figuring out other humans. However, it remains unknown to what extent individuals project their own personality structures onto others in person perception. This study examines whether such self-referential processes extend to influence complex personality structures. Two preregistered studies (n=118, n=72) examined self-reported personality traits and lay judgments of others’ personalities with and without faces. Both studies found evidence of self-projection of idiographic personality trait structure: Participants projected their own trait associations to others, which in turn, predicted the associations across face-based trait judgments. The effect could not be explained by individuals’ tendency to assume their own individual personality traits in others. This research underscores the critical role of individual self-concept in shaping social perceptions, with implications for understanding the processes of person perception and social cognition.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Oh, DongWon},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {self, assumed similarity, person perception, personality, social cognition, social perception, social psychology},

}

@misc{moore_effects_2024,

title = {The effects of referential continuity on novel word learning in bilingual and monolingual preschoolers},

url = {https://osf.io/a5zsw},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/a5zsw},

abstract = {Previous research suggests that monolingual children learn words more readily in contexts with referential continuity (i.e., repeated labeling of the same referent) than in contexts with referential discontinuity (i.e., referent switches). Here, we extended this work, testing monolingual and bilingual (N = 64) 3- and 4-year-olds’ novel word learning in an interactive tablet-based task. We predicted that bilinguals’ experience with language switches would buffer them against the attested challenges of referent switches on word learning. Unexpectedly, we found that monolinguals and bilinguals readily learned words in contexts of both referential continuity and referential discontinuity, and if anything performance was better in the referential discontinuity context. Overall, these results indicate that, at least for some learners under some conditions, referential discontinuity does not disrupt word learning. Our findings invite future research into understanding how and when referential continuity impacts language acquisition.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Moore, Charlotte and Williams, Madison and Byers-Heinlein, Krista},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{mentec_exploring_2024,

title = {Exploring the {Role} of {Valence} in {Conscious} {Perception}: {Insights} from {Similarity} {Judgments} and {Deep} {Learning} {Models}},

shorttitle = {Exploring the {Role} of {Valence} in {Conscious} {Perception}},

url = {https://osf.io/j5mdk},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/j5mdk},

abstract = {Recent theories claim that valence plays an important role in conscious perception (eg. Barrett \& Bar, 2009). Inspired by these theories, we tested how valence judgments relate to similarity judgments and whether they correlate with different stages of processing in deep neural networks (DNNs). To support the hypothesis that all perception is valenced, we focused on micro-valence, (Lebrecht et al., 2012). Forty-seven participants provided similarity and valence judgments for 120 images of everyday objects using the odd-one-out task and the birthday task (Lebrecht et al., 2012). For the same images, we extracted activations from the layers of DNNs trained to classify objects. Representation similarity analysis (Hebart et al. 2020) and multidimensional scaling analyses highlight the role of valence in the similarity space. Further, DNN analysis showed that perceptual features of the stimuli contributed to both valence and similarity processing. Most importantly, valence correlated with activations in the early DNN layers, suggesting a role of low-level visual features in valence computation. These results indicate that valence computation may occur in early visual processing. They also show that valence is involved in similarity judgments, corroborating recent claims for the functional role of conscious experience (Cleeremans \& Tallon-Baudry, 2022).},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-16},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Mentec, Inès and Ivanchei, Ivan and Cleeremans, Axel},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {Affect, Conciousness, Deep neural networks, Phenomenology, Similarity, Valence},

}

@misc{hong_re-evaluating_2024,

title = {Re-evaluating {Fictional} {Narratives}: {Cognitive} and ({Cultural}) {Evolutionary} {Perspectives} on the {Absence} of {Fictionality} in {Human} {Societies}},

shorttitle = {Re-evaluating {Fictional} {Narratives}},

url = {https://osf.io/8hnu4},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/8hnu4},

abstract = {In this article, I argue that fictionality—understood as a form of "make-believe" that requires the audience to suspend disbelief—has been largely absent throughout most of human history. This is due to two key factors: 1) humans are not psychologically predisposed to recognize fictionality, as it is cognitively demanding, and 2) traditional societies often have worldviews that allow for promiscuous causal possibilities, preventing narratives from being marked as fictional by their implausibility. I review extensive ethnographic and historical evidence suggesting that stories we now consider fictional were largely regarded as factual accounts of the past or attempts at such accounts. Additionally, I offer a critical discussion of how the absence of fictionality in diverse human societies impacts evolutionary theorizing about fictionality, as well as the broader cognitive and social consequences of (the lack of) fictional narratives.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Hong, Ze},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{caviola_moral_2024,

title = {Moral {Psychology} and {Utilitarianism}},

url = {https://osf.io/gfznr},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/gfznr},

abstract = {According to utilitarianism, we should improve the lives of humans and other sentient beings as much as possible. As an abstract ideal, utilitarianism has a natural appeal and may even sound like simple common sense. But utilitarianism has some implications—some merely theoretical, some very practical—that are counter-intuitive. When utilitarianism runs counter to our moral intuitions, is that because of a problem with utilitarianism or with our moral intuitions? In this article, we discuss the different ways in which human moral psychology and behavior deviate from what utilitarianism prescribes. We focus on psychological deviations from key aspects of utilitarianism: impartiality, maximization, consequentialism, and aggregate-welfarist values. Finally, we consider the normative implications of psychological science for utilitarianism. We conclude that the science of morality cannot show that utilitarianism is correct but that it can cast doubt on certain intuitive arguments against utilitarianism.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Caviola, Lucius and Greene, Joshua D.},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{grayson_ironic_2024,

title = {Ironic {Effects} of {Negative} {Gossip} in {Driving} {Inaccurate} {Social} {Perceptions}},

url = {https://osf.io/9fp5q},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/9fp5q},

abstract = {Gossip is often stereotyped as a frivolous social activity, but in fact can be a powerful tool for discouraging selfishness and cheating. In economic games, gossip induces people to act more cooperatively, presumably to avoid the cost of accruing a negative reputation. Might even this prosocial sort of gossip carry negative side effects? We propose that gossip might protect communities while simultaneously giving people the wrong idea about who’s in them. Specifically, gossipers might disproportionately share information about cheaters in their midst, driving cynical perceptions among receivers of that gossip. To test these predictions, we first reanalyzed data from a prior study in which people played a public goods game and could gossip about their fellow players. These participants indeed produced negatively skewed gossip: writing much more frequently about cheaters than cooperators, even when most people in their public goods game groups acted generously. To examine the effect of this gossip on cynicism, we ran a new experiment in which a second generation of participants read these gossip notes, and then prepared to play their own public goods game. Gossip recipients inferred that the groups that produced these notes acted significantly more selfishly than they truly had–becoming both cynical and inaccurate based on gossip. However, this gossip did not affect second generation participants’ forecasts of how their own group would behave, nor their own cooperative choices. Together, these findings suggest that gossip skews negative, and, therefore, encourages outside observers to draw more cynical conclusions about groups from which it comes.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Grayson, Samantha and Feinberg, Matthew and Willer, Robb and Zaki, Jamil},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {Gossip, Prosocial Behavior},

}

@misc{silvanto_aphantasia_2024,

title = {Aphantasia as suboptimal interoception and emotion processing},

url = {https://osf.io/bxkur},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/bxkur},

abstract = {Studies on mental imagery often rely on low-level, easily quantifiable stimuli to measure specific sensory features. However, this approach may not capture the rich, multisensory nature of real-world imagery, which integrates sensory details with emotions and bodily sensations. It is proposed that this broader perspective on internal states is crucial for understanding aphantasia—the inability to create vivid mental images. Our preliminary evidence suggests that aphantasia is linked to reduced interoceptive attention, raising the possibility that aphantasia reflects suboptimal ability to attend to and engage with internal signals, which are necessary for normal imagery experience. This conceptualisation of aphantasia in terms of interoception explains its links with alexithymia and autobiographical deficits.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Silvanto, Juha},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{grossmann_social_2024,

title = {The social self in the developing brain},

url = {https://osf.io/qs8dx},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/qs8dx},

abstract = {The notion that the self is fundamentally social in nature and develops through social interactions has a long tradition in philosophy, sociology, and psychology. However, to date, the early development of the social self and its brain bases in infancy has received relatively little attention. This presents a review and synthesis of existing neuroimaging research, showing that infants recruit brain systems, involved in self-processing and social cognition in adults, when responding to self-relevant cues during social interactions. Moreover, this review draws on recent research, demonstrating the early developmental emergence and social embeddedness/dependency of the default-mode network in infancy, a brain network considered of critical importance to the sense of self and social cognition. This stands in contrast to research pointing to the relatively late ontogenetic emergence of the conceptual self, by about 18 to 24 months of age, as seen in the mirror-self recognition test. Based on this review and synthesis, the social self first hypothesis (SSFH) is formulated, presenting an integrated view, arguing for the early ontogenetic emergence of the social self and its brain basis. This developmental account informs and extends existing evolutionary thinking, emphasizing the primary role that social interdependence has played in the evolution of the human mind.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Grossmann, Tobias},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{dumbalska_reference_2024,

title = {Reference dependence arises due to contextual shifts in both perception and judgment},

url = {https://osf.io/qpy2w},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/qpy2w},

abstract = {Reference dependence is a phenomenon where decisions about a current stimulus are biased by previously experienced, and currently irrelevant, stimuli. The ubiquity of reference dependence has been extensively documented. Yet, consensus on its computational origins remains elusive. Previous theoretic accounts have proposed that context influences behavior because it distorts our perception (how we experience the world), judgment (the standards against which we judge it) or action (how we respond to it). We carried out a series of carefully controlled experiments that pitted each of these proposals against one another by manipulating response bias and stimulus timing (Exp. 1), and jointly measuring decision bias and sensitivity (Exp. 2a-c) for decisions about stimulus lightness, size and numerosity. We found that reference dependence persists in the absence of influences stemming from action; it is attributable to contextual changes to both perception and judgment. Using computational modelling, we quantified the proportion of the reference dependence effect driven by each of those and found that it varies with stimulus type, with a relatively larger perception share for lower-level sensory stimulus properties like lightness. On average, more than half of the observed reference dependence effect size can be attributed to contextual changes to judgment. Understanding the computational mechanisms underlying reference dependence is critical for translational efforts to counterbalance the downstream, real-world consequences of this phenomenon.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Dumbalska, Tsvetomira and Smithston, Hannah},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

}

@misc{savelson_learned_2024,

title = {Learned {Distractor} {Rejection}: {Robust} but {Surprisingly} {Rapid}},

shorttitle = {Learned {Distractor} {Rejection}},

url = {https://osf.io/5n7ke},

doi = {10.31234/osf.io/5n7ke},

abstract = {The ability to reduce the distraction associated with repetitive irrelevant stimuli is critical to goal-directed navigation of the visual environment. Research has supported the existence of such an ability, which has often been referred to as learned distractor rejection (Vatterott \& Vecera, 2012). However, despite being theoretically relevant to many prominent accounts of distractor ignoring, few studies have directly tested learned distractor rejection since its conception. In the current study we present three direct replications of Vatterott and Vecera’s method that were separately conducted by two independent groups of researchers. Using the conventional split-block analysis, all three replications produce nearly identical results that fail to replicate the original study’s finding. However, using analyses on a finer-grained timescale we found compelling evidence for the existence of a learned ignoring of salient distractors. Critically, this learning occurred much more rapidly than has been previously assumed, taking only 2-3 encounters with the distracting item before efficient rejection emerged.},

language = {en-us},

urldate = {2024-09-25},

publisher = {OSF},

author = {Savelson, Isaac and Hauck, Christopher and Lien, Mei-Ching and Ruthruff, Eric and Leber, Andrew B.},

month = sep,

year = {2024},

keywords = {attentional capture, learned distractor suppression},

}